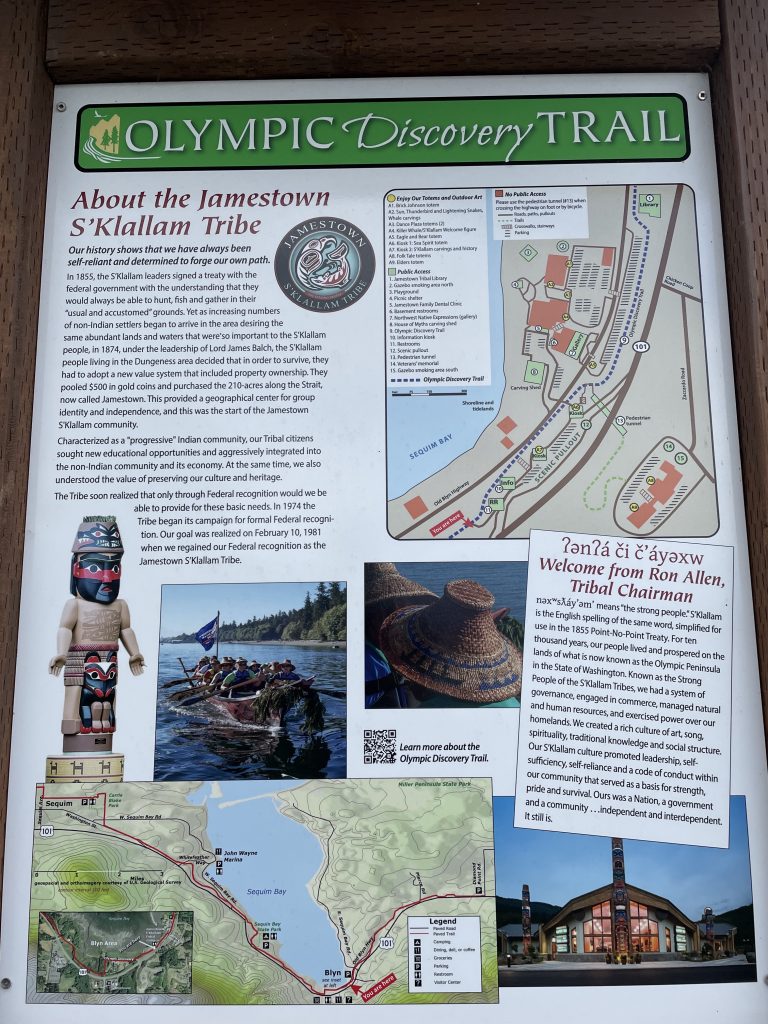

This past June I spent 4 days biking on the Olympic Peninsula on the ancestral lands of the nəxʷsƛ̕ay̕əm (S’Klallam) people. S’Klallam is the anglicized version of nəxʷsƛ̕ay̕əm and means “strong or mighty people”. Today the S’Klallam are politically divided into three reservations: Lower Elwha Klallam, Jamestown S’Klallam, and the Port Gamble S’Klallam tribes. There are different spellings of the word S’Klallam; Jamestown and Port Gamble use the spelling “S’Klallam” and the Lower Elwha Klallam omit the S’. The 4 days were magical, relaxing, challenging, and ended up being a personal reminder of the significance of the Washington Wildlife Recreation Program (WWRP). This trip was funded by a BIPOC Bikepacking grant from the non-profit, Bikepacking Roots, that I received in early 2021. Due to a bike industry shortage, wanting to not overcomplicate logistics, and COVID I decided to keep the plan simple, and car camp at Fairholme for 4 nights and bike as much of the Olympic Discovery Trail as I could.

Day 1

My partner Lindsay and I headed out to first come first serve Fairholme campground on the shore of Lake Crescent Wednesday morning, met up with our friend Becca, and surprisingly found the campground to be fairly empty. We waited out the lunchtime downpour and jumped on the Olympic Discovery Trail heading west from the campground toward Forks. The trail is in amazing shape and mostly paved for 10 miles winding through the beautiful Olympic National Forest with tons of Douglas Firs surrounding us and crossing the Sol Duc River once. We decided to turn around when the trail ended at Cooper Ranch Road, giving us a 20-mile roundtrip ride, through rain showers and sun.

Sol Duc River

Trail is well marked

Olympic Discovery Trail heading West

Day 2

Starting out from the campground we headed east on the Spruce Railroad Trail, which travels through multiple WWRP grant sites along the majestic Lake Crescent. The trail was recently re-opened following the clearing of a landslide and restoration of the Daley-Rankin Tunnel. The McFee tunnel was just short enough where we didn’t need to use a headlight. We rode the Spruce Railroad Trail 10 miles to its eastern end and then hopped onto a service road which took us to the Olympic Adventure Trail (OAT): 25 miles of double and single track through a very scenic, hilly, and lush forest. We had views of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Canada, Crescent Bay and Olympic National Forest. Along the OAT we passed a brother and sister working on a volunteer trail maintenance crew who warmly welcomed us to the trail and suggested routes nearby. We decided to only do a portion of the OAT and turned back toward camp because we were planning on riding the rest of the trail starting from the opposite eastern side in a few days. The beauty of out and back rides is that you get to see the trail and the views twice but from different perspectives and possibly experience it in different weather. Something you might have missed on the way out you catch on the way back. We rode out 15 miles in sunny weather and returned in a classic Peninsula downpour.

Spruce Railroad Trail along Lake Crescent

Daley-Rankin Tunnel

McFee Tunnel

Forest Service road to OAT

Recent trail maintenance on the OAT

Day 3

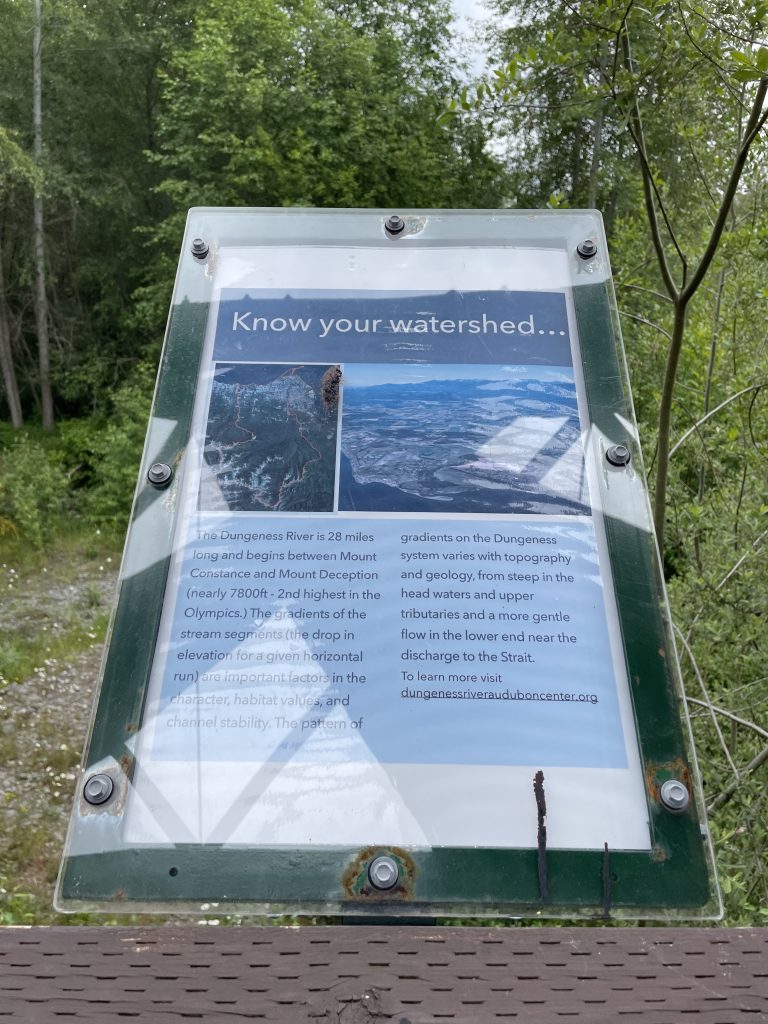

To try and escape the forecasted rain, we decided to put the bikes in the car and head to Sequim in hope of taking advantage of the Olympic rain shadow. We parked at Robin Hill County Park, which is a popular shady lunch spot for folks traveling along the Olympic Discovery Trail. As we were about to get on the trail and clouds started to roll in, we met two girls from Portland who were biking east to west on the ODT from Port Townsend to the Pacific. Feeling inspired by the two we started riding east on the ODT into the incoming rain–the rain shadow plan was not working in our favor. We rode through gusting winds and a downpour before the weather started to clear as we crossed the Dungeness River on the restored Railroad Bridge, which was funded by the WA State Recreation & Conservation Office Salmon Recovery Funding Board and sponsored by the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe. The bridge and river are beautiful. Even in the wind and rain a bunch of families and individuals were enjoying the views and natural history interpretive signs. The Jamestown S’Klallam tribe sponsored the expansion of the Railroad Bridge Park through a WWRP Local Parks grant by acquiring 18 acres of land along the Dungeness River to allow for public to access the area and to implement habitat restoration and water conservation projects.

We continued along the Sequim portion of ODT and soon were biking under blue skies along another portion of beautiful green trail funded by the WWRP Trails grant. This portion of the trail was flat with a slight decline down to Sequim Bay, where we entered the Jamestown S’Klallam reservation and their segment of the ODT. We stopped in at the Northwest Native Expressions art gallery and gift shop and purchased Native Peoples of the Olympic Peninsula, written by the Olympic Peninsula Intertribal Cultural Advisory Committee. Riding back toward Robin Hill County Park over the many bridges, different land ownerships, and past volunteer trail workers, we chatted about the diverse groups that had to come together to make the trail possible and the stewardship to maintain it. We returned to the car stoked on our 30-mile ride just as the rain started again.

Dungeness River

Railroad Bridge

Know your watershed

Johnson Creek Railroad Trestle

Jamestown S’Klallam Reservation

Day 4

We saved the most challenging and rugged portion of the ODT for the last day. The Olympic Adventure Trail (OAT) was everything we had expected from its name. Our shorter ride on the western end gave us a nice preview of what we were getting ourselves into coming from eastern entrance. The OAT is a 25-mile single and double track alternative to the paved rail grade ODT route between the Elwha River and Lake Crescent. We ran into the brother and sister volunteers who we met on Day 2, this time biking and enjoying the trail themselves. We rode the trail on gravel bikes–possibly would have been a bit more comfortable on a hardtail mountain bike–but we had an absolute blast! My favorite day of the trip and also the sunniest!

Wonderful tree cover

View of the Strait of Juan de Fuca

Looking south into the Olympic National Forest

I left the peninsula grateful for the outdoor spaces available to recreate on, those who have volunteered their time to build and maintain the trails we rode on, and for the diverse communities who came together to make the creation of the ODT possible. I also reflected on what the WWRP does best. While providing public funding for new local and state parks, wildlife habitat, and preservation of working farm and forest lands are the tangible benefits, I think the most powerful thing the WWRP grant program does is bring different communities together to build sustainable relationships and work toward a common goal where everyone involved benefits. As outdoor recreation in Washington state continues to grow, and as we continue to leave a lasting footprint on the earth, it’s going to be imperative that the grant program bring together voices who represent all who inhabit the outdoors to work together so that generations to come have a healthy place to live and thrive.