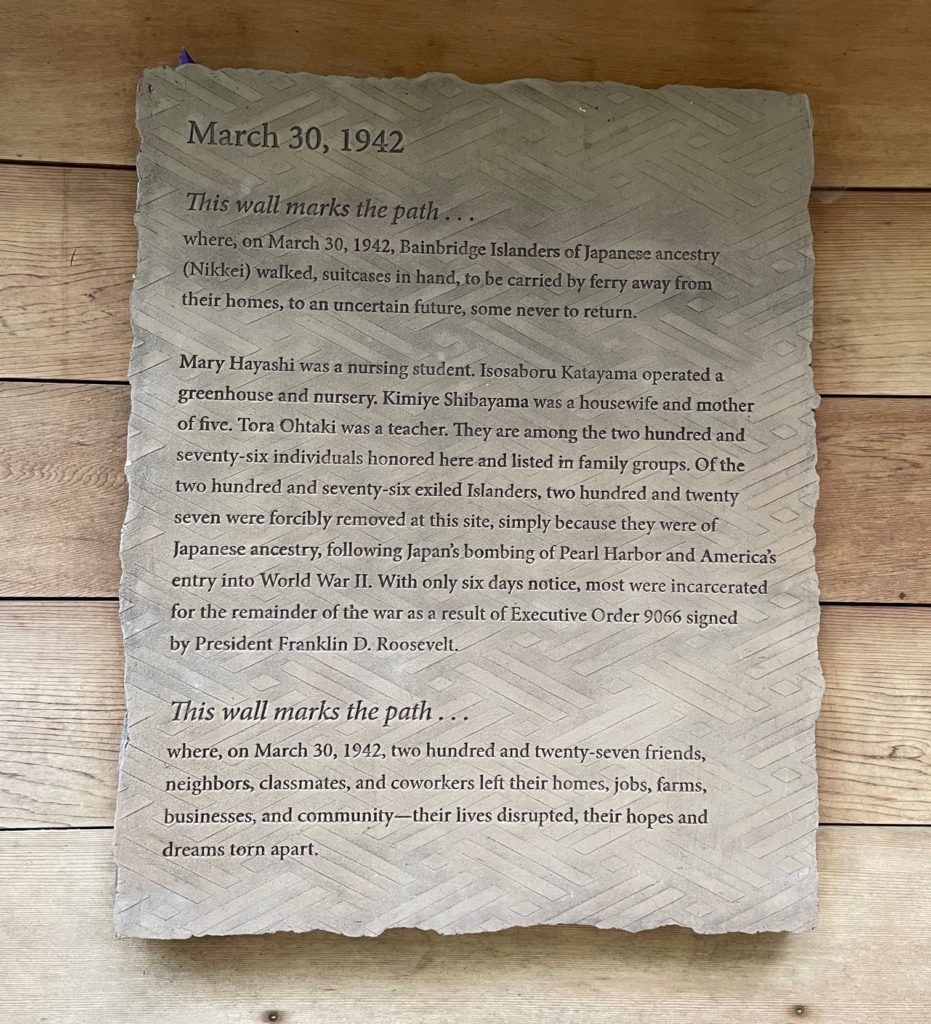

80 years ago, on February 19, 1942 President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing a forceable removal and imprisonment of over 120,000 Japanese-Americans in concentration camps across the US in reaction to the Empire of Japan bombing Pearl Harbor in the Territory of Hawaii on December 7, 1941. By March 30 the first Japanese-Americans to be imprisoned were placed on a ferry leaving Bainbridge Island. “Two hundred and twenty-seven friends, neighbors, classmates, and coworkers left their homes, jobs, farms, businesses, and community – their lives disrupted, their hopes and dreams torn apart.” These words are written on the old-growth red cedar and granite story wall at the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial located on the ancestral land of the Suquamish and Coast Salish people.

“Where, on March 30, 1942, Two hundred and twenty-seven friends, neighbors, classmates, and coworkers left their homes, jobs, farms, businesses, and community – their lives disrupted, their hopes and dreams torn apart.”

The story wall, 276 feet long–one foot for each person of Japanese descent who was exiled from Bainbridge–sits in the center of the memorial and winds down the Eagledale ferry dock landing site. The wall, created by a Seattle architect Johnpaul Jones, follows the exact path the Japanese from Bainbridge walked to be carried away by ferry from their homes.

The WWRC team visited the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial in November 2021 and had the privilege to be given a tour by Clarence Moriwaki and Carolyn Hart. Clarence is the third generation Japanese-American who led the development and stewardship of the memorial until becoming a Bainbridge Island council member in 2021, and Carolyn is a volunteer at the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community (BIJAC). The memorial sits in Pritchard Park, a 2005 WWRP Local Park grant recipient. It is surrounded by tall cedar, fir, and alder trees and includes the tallest cherry tree in the state. It’s a very deliberate, powerful, and yet tranquil space. The crushed granite that makes up the walking path down to the water intentionally ties in the granite in the wall. The crushed rock under your shoes allows you to hear your own footsteps and imagine the footsteps of those who were forced off the Island in 1942.

Clarence noted that when visiting the memorial guests will notice there is very little Kanji, Japanese writing characters. The only Kanji visible is at the entrance because it symbolizes the Bainbridge Japanese-Americans’ beginning– their ancestry. The use of mostly English is intentional to illustrate that this was an American story. These folks who were incarcerated were Americans. The theme of the memorial, written at the entrance in Japanese, is “Nidoto Nai Yoni,” “Let It Not Happen Again.” It is a reminder of a terrible time in history, the need to be forever vigilant for the assumed rights as citizens, and to give hope that something like this will never happen again.

Nidoto Nai Yoni

“Let It Not Happen Again”

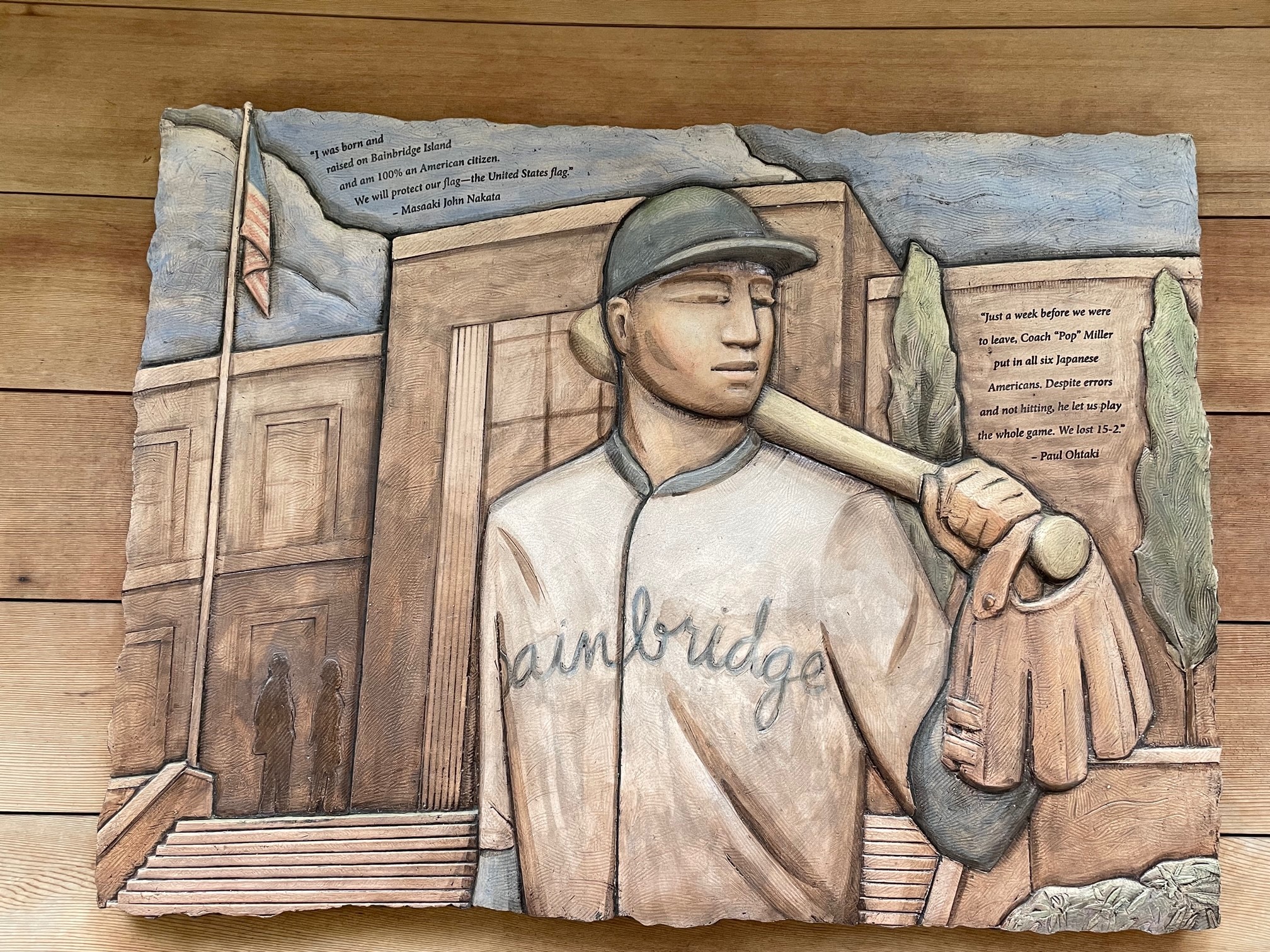

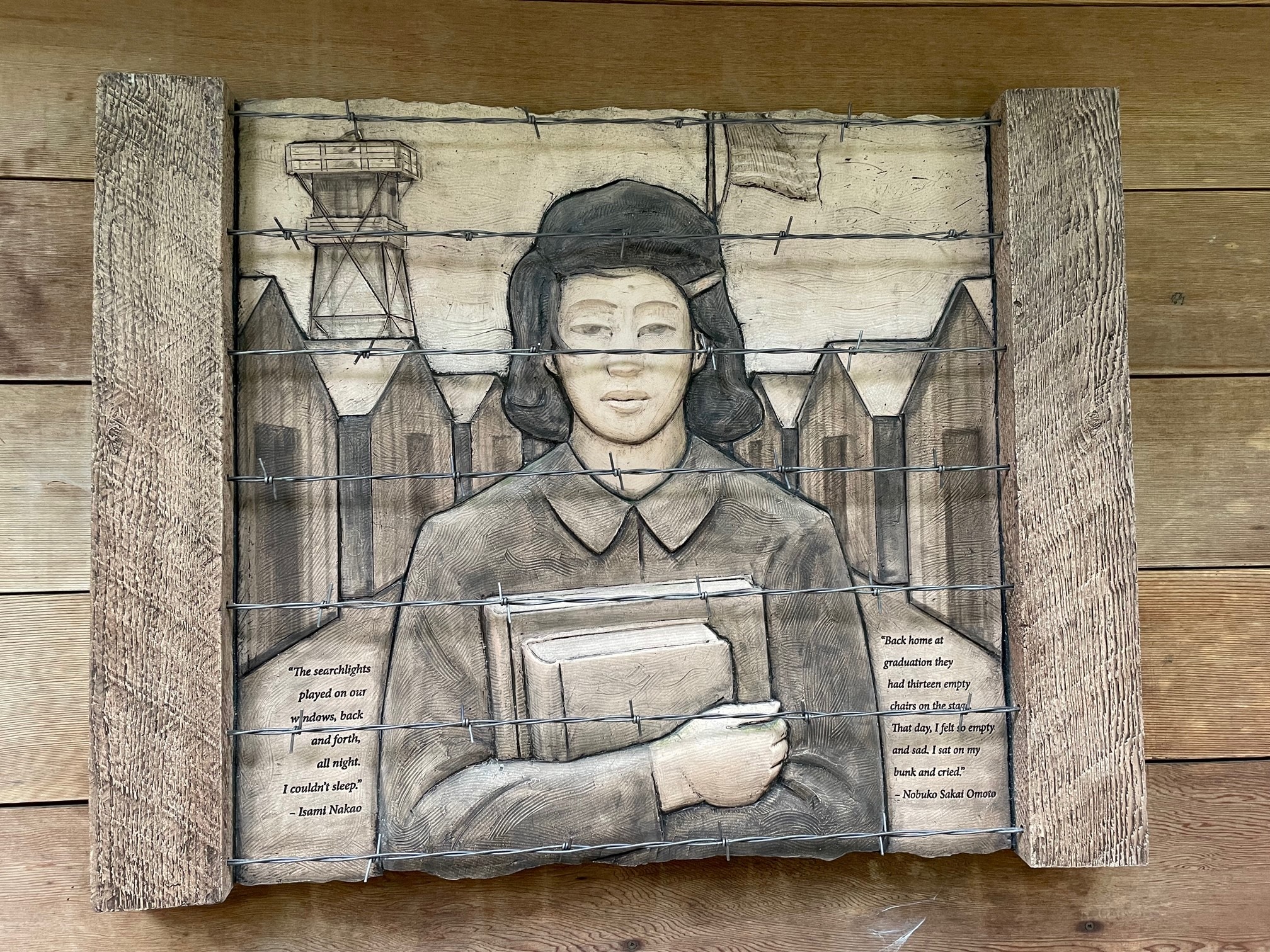

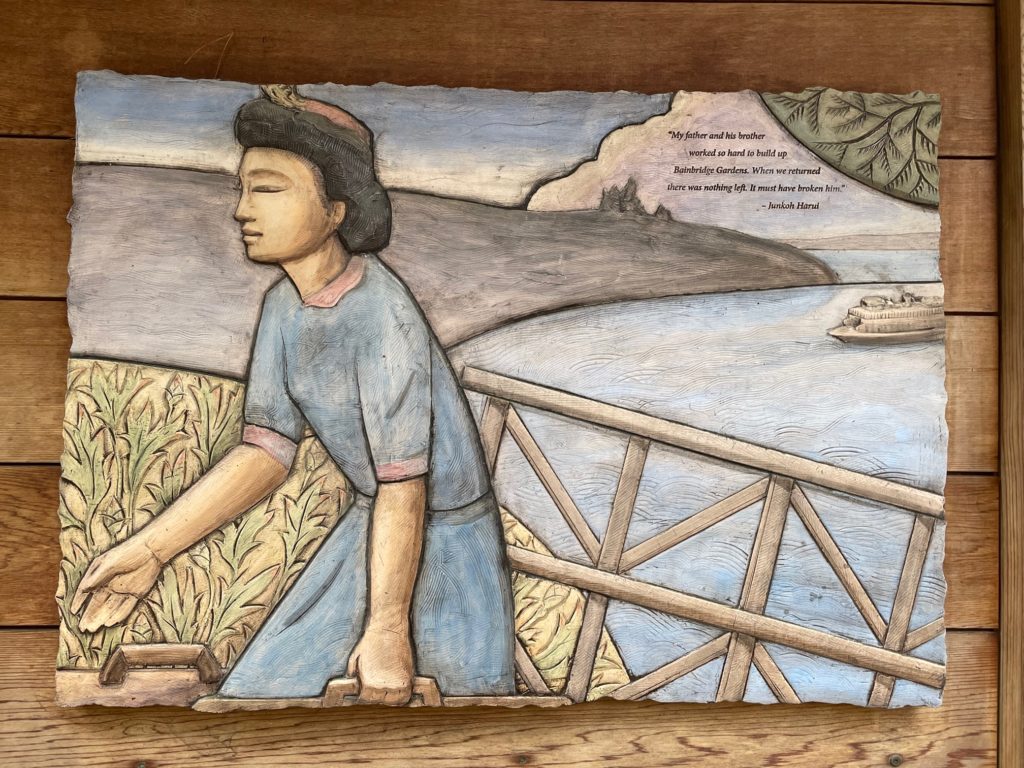

When walking down the path you notice the wall is curved. Clarence shared that this is to represent how time is sinuous. The curves in the wall evoke the experiences of the 276 Japanese-Americans from their lives on Bainbridge Island, to being removed from their homes and shipped to the concentration camps in Manzanar in central California, then to Minidoka in Idaho, and finally their return to Bainbridge after being released. The names and ages of all 276 Japanese-Americans who were exiled from the island are etched onto terracotta planks and attached to the wall in family groupings. Carefully selected quotations are also etched into paintings among the names to help tell their stories. It is beautiful and fascinating to see how the architecture of this space shows such a painful time with such compassion and tranquility.

“I felt like a second-class citizen, to be herded onto the boat by soldiers with bayonets. It was…the most humiliating experience of my life.”

Isami Nakao

I was most drawn to a gap in the cedar wall where there is a large basalt rock, distinct from the granite that makes up the foundation of the story wall. The basalt represents the Minidoka camp, where most of the Bainbridge Islanders were transferred after arriving at Manzanar. Minidoka was located in Southern Idaho where basalt is very common. The break in the wall signifies the gap in time where the Japanese-Americans were away from Bainbridge Island at internment camps. Aesthetically, the gap looks out of place, signifying the grave mistake and injustice the United States Government made incarcerating 1,200 Japanese-Americans.

Where the wall begins again represents their release in 1945 and return home. It celebrates the island community, which defended its Japanese-American friends and neighbors, supported them while they were away, and welcomed them home. You will see stories on the wall of the tight Bainbridge community watching after Japanese family farms and welcoming their neighbors home. There are also stories of those returning home who were not as fortunate and came back to nothing.

“We put the farm under Mr. Raber’s name while we were gone. We came back, he returned it to us.”

Noburo Koura

My father and his brother worked so hard to build up Bainbridge Gardens. When we returned there was nothing left. It must have broken him.”

Junkoh Harui

If you have not yet visited the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial, I encourage you to make the trip. It’s one thing to know about what happened in 1942, but it’s another thing to walk in the footsteps of those who were exiled from the island and imagine being forced to walk away from your home because of your ancestry not knowing what the future would hold.