By volunteer Alysen Laakso, who recently moved to Pierce County from Austin, Texas.

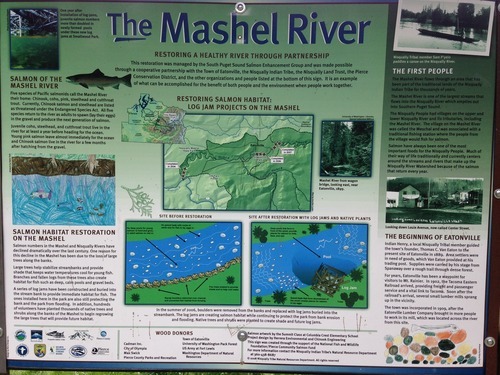

During the development boom of the mid-2000s, the town of Eatonville and the Nisqually Tribe worried that land around the Mashel River would be lost, threatening critical salmon habitat.

As part of an effort to conserve and protect that land, the town of Eatonville successfully applied for a Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program grant to ultimately buy over 120 acres of land to protect the salmon. I recently interviewed Nick Bond, who worked as an Eatonville planner during the early days of the restoration project.

This story is a shining example of cooperation and communication between two communities as they worked together to protect this iconic fish.

The idea for the project was spawned by the Nisqually Tribe and sponsored by the city of Eatonville. For years the tribe serve as a technical advisor on Nisqually River habitat restoration, writing nationally approved restoration plans for the region.

In 2007, seeking to expand habitat restoration and conservation, the tribe asked the town to help them by applying for the grant to allow for land acquisition and safeguarding that land against low-density development.

Nearly $1 million in matching funds came from came from the Nisqually Land Trust, through funding provided by Pierce County Conservation Futures. The Land Trust worked closely with Eatonville to coordinate the purchases and the land match.

Additionally, the Nisqually Tribe was able to use their research to help Eatonville prove the importance of the Mashel River for salmon spawning grounds. Their expertise and land matching was a major factor in ensuring the grant money was awarded to the town.

The groups recognized that both communities relied on the natural resources the river offered. The Nisqually Tribe recognized that the city uses the Mashel River. Eatonville’s mayor remembered the salmon runs from his childhood and supported the tribe’s conservation efforts for the fish that are crucial for the culture and economy. According to Mr. Bond, throughout the project, everyone from city council members to land owners and private citizens supported the conservation efforts and the protection of the salmon habitat. This meant that once the grant was awarded, Eatonville was easily able to acquire the lands from willing sellers.

In the end, because Eatonville, the Niqually Land Trust and the Nisqually Tribe focused on open communication and building a common cause, they were able to successfully ensure long-term conservation for a vital ecosystem and take the necessary first steps to protect the salmon population.

The work is ongoing, contributing to a much larger regional effort.

“The WWRP project is just one portion of a much larger project, the Mashel Shoreline Protection Initiative, that has now protected nearly three miles of the Mashel River through Eatonville, and some 27 properties, and includes eight different funding partners, at the local, tribal, county, state, and federal levels,” said Joe Kane, Executive Director of the Nisqually Land Trust "Without this larger context, it is unlikely that the WWRP project would have succeeded.“

So far the city and the tribe have overseen the construction of over 50 log jams, which help create deep pools beneficial to the salmon runs. Now the town and tribe are continuing their successful partnership to develop plans for limited trails to allow people access to enjoy, appreciate, and learn from the Mashel River Greenbelt.

Alysen recently graduated with her master’s degree in environmental non-profit and is now taking her first steps in building her career the field. She regularly volunteers with non-profits in Puget Sound and is always looking for new ways to support environmental causes and wildlife conservation. She is especially focused on where community meets the environment and enjoys learning about how communities come together to support and protect their local ecosystems and natural spaces. This is her first article for the Wildlife and Recreation Coalition.

*This story has been corrected from an earlier version to accurately reflect the involvement of the Nisqually Land Trust.